bash скрипты mac os

How to make a simple bash script (Mac)

How to make a simple bash script (Mac)

The first step to make a simple bash script is writing the script.

Open Text Edit, found in Applications, once in Text Edit, click “New Document”.

Next, write the Bash Script, as below:

#!/bin/bash tells the terminal that you are using bash shell

echo hello world prints out “hello world” in the terminal

Once you have written the script, you have to convert the document into plain text.

Select “Format” from the Menu and then click “Make Plain Text.”

Next click “File” and then “Save.”

Name it whatever you would like, but remember how you typed the name because we are going to be using that exact name in the terminal.

For the purpose of this tutorial, I am going to name it “FirstScript”, and I am going to save it in my Documents folder.

Also you have to uncheck the box that says “If no extension is provided, use ‘.txt’.”

Next you are going to open the Finder.

Search for the name of the script you just wrote, or navigate to the file.

Once you found it, right click on it (CTRL + click) and click “Get Info”.

Look on the very bottom right of the opened info window, and you will see a Lock icon that should appear locked.

Click it, and if you have a password on your computer it will ask you for your password to unlock it, otherwise it will just unlock.

Once that is done, you have to open Terminal and navigate to the folder you put the document in.

In the terminal, for my case, I am going to type in

Now we have to change the file we saved to an executable file. Type in chmod 700(file Name). I’m going to type in

chmod 700 FirstScript

This will change it into an executable file.

Shell Scripting Primer

Shell Script Basics

Writing a shell script is like riding a bike. You fall off and scrape your knees a lot at first. With a bit more experience, you become comfortable riding them around town, but also quickly discover why most people drive cars for longer trips.

Shell scripting is generally considered to be a glue language, ideal for creating small pieces of code that connect other tools together. While shell scripts can be used for more complex tasks, they are usually not the best choice.

If you have ever successfully trued a bicycle wheel (or paid someone else to do so), that’s similar to learning the basics of shell scripting. If you don’t true your scripts, they wobble. Put another way, it is often easy to write a script, but it can be more challenging to write a script that consistently works well.

This chapter and the next two chapters introduce the basic concepts of shell scripting. The remaining chapters in this document provide additional breadth and depth. This document is not intended to be a complete reference on writing shell scripts, nor could it be. It does, however, provide a good starting point for beginners first learning this black art.

Shell Script Dialects

There are many different dialects of shell scripts, each with their own quirks, and some with their own syntax entirely. Because of these differences, the road to good shell scripting can be fraught with peril, leading to script failures, misbehavior, and even outright data loss.

To that end, the first lesson you must learn before writing a shell script is that there are two fundamentally different sets of shell script syntax: the Bourne shell syntax and the C shell syntax. The C shell syntax is more comfortable to many C programmers because the syntax is somewhat similar. However, the Bourne shell syntax is significantly more flexible and thus more widely used. For this reason, this document only covers the Bourne shell syntax.

The second hard lesson you will invariably learn is that each dialect of Bourne shell syntax differs slightly. This document includes only pure Bourne shell syntax and a few BASH-specific extensions. Where BASH-specific syntax is used, it is clearly noted.

The terminology and subtle syntactic differences can be confusing—even a bit overwhelming at times; had Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz been a programmer, you might have heard them exclaim, «BASH and ZSH and CSH, Oh My!» Fortunately, once you get the basics, things generally fall into place as long as you avoid using shell-specific features. Stay on the narrow road and your code will be portable.

Some common shells are listed below, grouped by script syntax:

Bourne-compatible shells

C-shell-compatible shells

bcsh (C shell to Bourne shell translator/emulator)

Many of these shells have more than one variation. Most of these variations are denoted by prefixing the name of an existing shell with additional letters that are short for whatever differentiates them from the original shell. For example:

About the C Shell

However, the C shell scripting language has its uses, particularly for writing scripts that set up environment variables for interactive shell environments, execute a handful of commands in order, or perform other relatively lightweight chores. To support such uses, the C shell syntax is presented alongside the Bourne shell syntax within this «basics” chapter where possible.

Shell Variables and Printing

What follows is a very basic shell script that prints “Hello, world!” to the screen:

The first thing you should notice is that the script starts with ‘ #! ’. This is known as an interpreter line. If you don’t specify an interpreter line, the default is usually the Bourne shell ( /bin/sh ). However, it is best to specify this line anyway for consistency.

If you’d like, you can try this script by saving those lines in a text file (say “hello_world.sh”) in your home directory. Then, in Terminal, type:

Of course, this script isn’t particularly useful. It just prints the words “Hello, world!“ to your screen. To make this more interesting, the next script throws in a few variables.

You should immediately notice that variables may or may not begin with a dollar sign, depending on how you are using them. If you want to dereference a variable, you precede it with a dollar sign. The shell then inserts the contents of the variable at that point in the script. For all other uses, you do not precede it with a dollar sign.

Important: You generally do not want to prefix the variable on the left side of an assignment statement with a dollar sign. Because FIRST_ARGUMENT starts out empty, if you used a dollar sign, the first line:

C Shell Note: The syntax for assignment statements in the C shell is rather different. Instead of an assignment statement, the C shell uses the set and setenv builtins to set variables as shown below:

Using Arguments And Variables That Contain Spaces

Take a second look at the script from the previous section:

By surrounding the string with double quote marks, the shell treats the entire string as a single argument to echo even though it contains spaces.

To see how this works, save the script above as test.sh (if you haven’t already), then type the following commands:

The second line above prints “Hello, world leaders and citizens!” because the quotation marks on the command line cause everything within them to be grouped as a single argument.

Notice also that there are similar quotation marks on the right side of the assignment statement:

With most modern shells, these double quotation marks are not required for this particular assignment statement (because there are no literal spaces on the right side), but they are a good idea for maximum compatibility. See Historical String Parsing in Historical Footnotes and Arcana to learn why.

When assigning literal strings (rather than variables containing strings) to a variable, however, you must surround any spaces with quotation marks. For example, the following statement does not do what you might initially suspect:

If you type this statement, the Bourne shell gives you an error like this:

The reason for this seemingly odd error is that the assignment statement ends at the first space, so the next word after that statement is interpreted as a command to execute. See Overriding Environment Variables for Child Processes (Bourne Shell) for more details.

Instead, write this statement as:

Using quotation marks is particularly important when working with variables that contain filenames or paths. For example, type the following commands:

Handling Quotation Marks in Strings

In modern Bourne shells, expansion of variables, occurs after the statement itself is fully parsed by the shell. (See Historical String Parsing in Historical Footnotes and Arcana for more information.) Thus, as long as the variable is enclosed in double quote marks, you do not get any execution errors even if the variable’s value contains double-quote marks.

However, if you are using double quote marks within a literal string, you must quote that string properly. For example:

C Shell Note: The C shell handling of backslashes within double-quoted strings is different. In the C shell, the previous example should be changed to:

prints the phrase “Hello, world “leaders”!”

Exporting Shell Variables

Normally, this is what you want. Most variables in a shell script do not have any meaning to the tools that they execute, and thus represent clutter and the potential for variable namespace collisions if they are exported. Occasionally, however, you will find it necessary to make a variable’s value available to an outside tool. To do this, you must export the variable. These exported variables are commonly known as environment variables because they affect the execution of every script or tool that runs but are not part of those scripts or tools themselves.

A classic example of an environment variable that is significant to scripts and tools is the PATH variable. This variable specifies a list of locations that the shell searches when executing programs by name (without specifying a complete path). For example, when you type ls on the command line, the shell searches in the locations specified in PATH (in the order specified) until it finds an executable called ls (or runs out of locations, whichever comes first).

The details of exporting shell variables differ considerably between the Bourne shell and the C shell. Thus, the following sections explain these details in a shell-specific fashion.

Using the export Builtin (Bourne Shell)

Generally speaking, the first time you assign a value to an environment variable such as the PATH variable, the Bourne shell creates a new, local copy of this shell variable that is specific to your script. Any tool executed from your script is passed the original value of PATH inherited from whatever script, tool, or shell that launched it.

With the BASH shell, however, any variable inherited from the environment is automatically exported by the shell. Thus, in some versions of OS X, if you modify inherited environment variables (such as PATH ) in a script, your local changes will be seen automatically by any tool or script that your script executes. Thus, in these versions of OS X, you do not have to explicitly use the export statement when modifying the PATH variable.

Because different Bourne shell variants handle these external environment variables differently (even among different versions of OS X), this creates two minor portability problems:

A script written without the export statement may work on some versions of OS X, but will fail on others. You can solve this portability problem by using the export builtin, as described in this section.

To guarantee that your modifications to a shell variable are passed to any script or tool that your shell script calls, you must use the export builtin. You do not have to use this command every time you change the value; the variable remains exported until the shell script exits.

Either of these statements has the same effect—specifically, they export the local notion of the PATH environment variable to any command that your script executes from now on. There is a small catch, however. You cannot later undo this export to restore the original global declaration. Thus, if you need to retain the original value, you must store it somewhere yourself.

In the following example, the script stores the original value of the PATH environment variable, exports an altered version, executes a command, and restores the old version.

The resulting variable will contain 1 if the variable is defined in the environment or 0 if it is not.

Overriding Environment Variables for Child Processes (Bourne Shell)

Because the BASH Bourne shell variant automatically exports all variables inherited from its environment, any changes you make to preexisting environment variables such as PATH are automatically inherited by any tool or script that your script executes. (This is not true for other Bourne shell variants; see Using the export Builtin (Bourne Shell) for further explanation.)

This problem is easily solved by overriding the environment variable PATH on a per-execution basis. Consider the following script:

Thus, to modify the PATH variable locally but execute a command with the original PATH value, you can write a script like this:

Using the setenv Builtin (C shell)

If you want your shell variables to only be available to your script, you should use the set builtin (described in Shell Variables and Printing ). The set builtin is equivalent to a simple assignment statement in the Bourne shell.

Notice that the local variable version requires an equals sign ( = ), but the exported environment version does not (and produces an error if you put one in).

To remove variables in the C shell, you can use the unsetenv or unset builtin. For example:

If you need to test an environment variable (not a shell-local variable) that may or may not be part of your environment (a variable set by whatever process called your script), you can use the printenv builtin. This prints the value of a variable if set, but prints nothing if the variable is not set, and thus behaves just like the variable behaves in the Bourne shell.

This prints X is «» if the variable is either empty or undefined. Otherwise, it prints the value of the variable between the quotation marks.

If you need to find out if a variable is simply empty or is actually not set, you can also use printenv to obtain a complete list of defined variables and use grep to see if it is in the list. For example:

The resulting variable will contain 1 if the variable is defined in the environment or 0 if it is not.

Overriding Environment Variables for Child Processes (C Shell)

Unlike the Bourne shell, the C shell does not provide a built-in syntax for overriding environment variables when executing external commands. However, it is possible to simulate this either by using the env command.

The best and simplest way to do this is with the env command. For example:

As an alternative, you can use the set builtin to make a temporary copy of any variable you need to override, change the value, execute the command, and restore the value from the temporary copy.

As a workaround, you can determine the path of the executable using the which command prior to altering the PATH environment variable.

Deleting Shell Variables

For the most part, in Bourne shell scripts, when you need to get rid of a variable, setting it to an empty string is sufficient. However, in long-running scripts that might encounter memory pressure, it can be marginally useful to delete the variable entirely. To do this, use the unset builtin.

The unset builtin can also be used to delete environment variables.

Also, in C shell, if you try to use a deleted variable, it is considered an error. (In Bourne shell, an unset variable is treated like an empty string.)

Copyright © 2003, 2014 Apple Inc. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Updated: 2014-03-10

[Mac OS X] Начинающим о работе в Терминале

В OS X обычный пользователь практически не сталкивается с необходимостью использовать командную строку, поскольку большинство его нужд покрывает то, что реализовано в графическом интерфейсе системы.

Другое дело, когда нужны некоторые скрытые возможности, которые недоступны из графического интерфейса. Собственно в этой рубрике мы частенько прибегаем к извлечению этих скрытых возможностей при помощи командной строки. А потому я и решил немного рассказать о программе Терминал и командной строке, а так же дать пару советов новичкам, которые позволят им ощущать себя в ней более комфортно.

Небольшое введение

Начнем с вопроса, что такое Терминал? Прежде всего, это приложение, внутри которого выполняется командный интерпретатор. Его еще часто называют интерфейсом командной строки. Он интерпретирует команды специального языка скриптов.

Пояснение слова скрипт

Правильнее «скрипт» следует называть сценарием, поскольку это одно из значений английского слова — sript. Да и фактически «скрипт» является сценарием. Но термин «скрипт» очень прочно устоялся среди программистов, а потому я немного нарушу правила русского языка и буду называть его именно – скрипт. Тем более что и само слово «сценарий» заимствовано русским языком и родным ему не является.

Языки скриптов бывают разные, но есть наиболее распространенный набор таких языков, а соответственно и их интерпретаторов.

В настоящее время bash – фактически стандарт де-факто в большинстве Unix-подобных систем.

Найти информацию обо всех перечисленных интерпретаторах несложно в «Википедии».

Командная строка

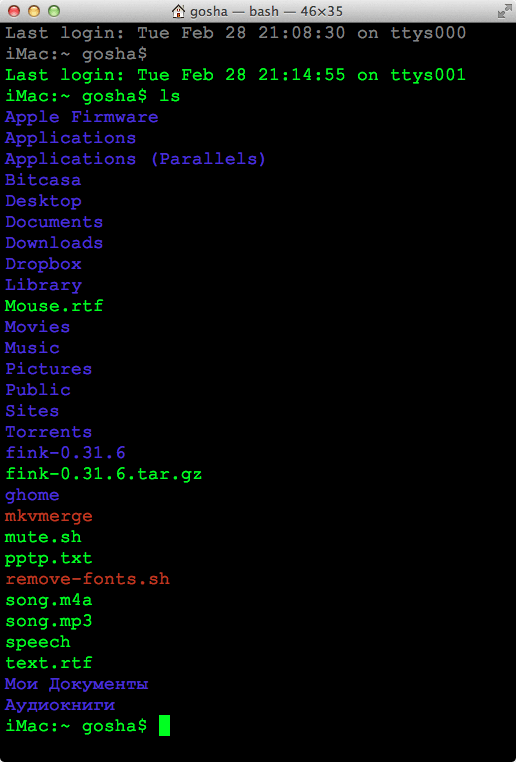

Когда вы запускаете программу Терминал, то видите в ее окне командную строку, которая в моей системе выглядит так:

Командная строка начинается с названия компьютера (у меня он называется iMac), затем следует название текущего каталога — по умолчанию открывается домашний каталог пользователя, который в Unix-системах обозначается знаком

Примечание: в заголовке окна Терминала вы видите текущий каталог (в данном случае это домашний каталог, а потому он обозначен домиком), затем имя пользователя, затем название используемого интерпретатора (в данном случае — bash ) и размер окна в символах.

Язык скриптов bash

Самой простой командой этого языка является запуск программы – она состоит только из имени файла программы и, если необходимо, то и полный путь до этого файла, а так же, возможно, с последующими за именем файла ключами и параметрами, которые дают различные указания выполняемой программе.

Небольшое, но важное пояснение

Посмотреть содержимое переменной PATH вы можете командой:

Естественно эту переменную можно настраивать, но какой-то особой необходимости в этом у обычного пользователя не возникает, а потому я опущу этот вопрос.

Ну а теперь перейдем собственно к советам.

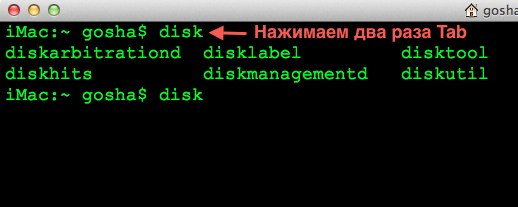

Совет 1 — автодополнение

При использовании командной строки очень часто приходится вводить имена файлов – обычно это файлы различных команд, и вводить имена файлов или каталогов, передаваемых в качестве параметра командам, которые необходимо набирать с указанием полного пути до них. И вот для того, чтобы не ошибиться при наборе, в bash имеется механизм, называемый автодополнением.

Примечание: в дальнейшем, для удобства, я буду называть имя файла команды просто командой. Это общепринятая практика.

Смысл этого механизма заключается в том, что когда вы начинаете набирать команду, вводите первые несколько букв и нажимаете клавишу Tab, в результате чего набор команды будет завершен автоматически. Это же работает и при наборе пути и имен файлов, передаваемых командам в качестве параметров.

Точно так же это действует и при наборе имен каталогов и файлов, передаваемых в качестве параметров командам.

И сразу небольшое отступление.

И еще одно отступление.

Итак, мы ознакомились с автодополнением. Этот инструмент позволяет очень быстро и безошибочно вводить команды. Между прочим, многие файловые операции (копирование, перемещение, переименование, удаление) бывают гораздо проще и их быстрее выполнить именно в командной строке, используя механизм автодополнения. 🙂

Совет 2 – история команд

Пользоваться историей команд очень просто – при помощи клавиш навигации — Стрела вверх и Стрелка вниз. Нажмите первую из них и вы увидите в командной строке предыдущую выполненную команду. Последующие нажатия этой клавиши будут последовательно выводить ранее выполненные вами команды. Соответственно вторая клавиша листает список выполненных команд в обратном направлении.

Так же, если вы ввели команду с ошибкой и попытались ее выполнить, то после получения сообщения об ошибке, гораздо проще бывает не вводить команду заново, а исправить ошибку в предыдущей, вызвав ее нажатием на клавишу Стрелка вверх, а затем внеся исправления.

Надеюсь, это небольшое введение в основы мира командной строки, не слишком вас утомило. 🙂

Консоль для маководов: Beyond the GUI

Доброго дня, уважаемые хабравчане-маководы!

Сегодня я расскажу как увеличить эффективность работы в Mac OS X за счёт использования консоли.

Лирическое отступление

Если Вы пришли из мира M$, то для начала неплохо бы поучить общие команды shell’а, например, по вот этому учебному пособию. Как минимум, нужно усвоить команды перехода по каталогам и способы запуска программ и скриптов.

Если Вы пришли в мир Mac OS из мира Linux’а и FreeBSD, то, скорее всего, знаете как минимум основы shell-скриптинга. Но и для вас в статье может оказаться кое-что интересное, ведь в маке есть уникальные консольные команды, которые так же полезно знать.

Вот о некоторых особенностях маковской консоли далее и пойдёт речь.

Начнём работу

Для начала избавимся от стандартного терминала. Ну, точнее, поставим другой — получше. Я лично предпочитаю iTerm2, который подходит для работы куда лучше системного. Хотя, и у него бывают интересные моменты (см. картинку вверху).

Далее нам могут понадобиться дополнительные инструменты, поэтому устанавливаем MacPorts (хотя, конечно, можно и другой менеджер пакетов). Теперь мы можем ставить нужные консольные утилиты с помощью простых команд. Например, ставим Midnight Commander (он в любом случае может пригодиться), набираем в iTerm2:

Ещё одно важное замечание: кури мануалы если что-то не понятно, набираем в консоли man команда — и получаем подробное описание команды. (Кстати, для выхода из просмотра мануала надо просто нажать Q).

Продолжаем знакомство с консолью. Команда open

И — опа! — скрытый файл открылся в TextEdit! Всё предельно просто.

Пара слов о бандлах

Способ первый, простейший:

Программа будет запущена и консоль будет свободна для дальнейших действий.

Способ второй, интересный:

Программа будет запущена, но консоль не освобидится — она будет ждать завершения программы и выводить всё, что программа захочет вывести в неё. То есть, таким образом можно посмотреть рабочий лог некоторых программ.

Ещё одно очень важное различие между этими двумя методами: второй позволяет запустить два экземпляра программы, в то время как первый активирует уже запущенную, буде такая имеется. Так что через консоль можно решить и эту проблему (хотя, скорее фичу) макоси: через Finder, док и лаунчер запустить два экземпляра программы нельзя, а вот из консоли — пожалуйста, хоть двадцать два.

Скрипт?

Пример простейший, но он демонстрирует главное: в скриптах сокрыта великая сила.

Скрипты AppleScript

Не буду углубляться в AppleScript, он заслуживает отдельной статьи, и даже не одной. Так что рекомендую почитать справку или гугл по нему.

Главное: Вы можете комбинировать shell-скрипты со скриптами AppleScript, чтобы добиться максимальной гибкости в работе! К примеру, я использую такие вот смешанные скрипты для автоматической стилизации образа диска: сам диск создаётся с помощью shell (см. ниже), а фон и расположение элементов в образе задаётся с помощью AppleScript.

Есть ещё Automator, но он совсем уж GUI-шный, так что в данной статье его рассматривать бессмысленно. Он, конечно, полезный, но до мощи консоли не дотягивает.

Кратко о других полезных командах Mac OS X

Полный (ну, почти) список уникальных для макоси команд можно найти в одной хорошей статье (хотя сведения там немного устарели), я же вкратце расскажу о наиболее интересных.

Одна беда — по-умолчанию говорит эта штука только по-английски.

Теперь снимем скриншот командой из консоли.

Так же textutil умеет преобразовывать кодировки.

Файндер автоматически перезапустится и теперь будет отображать скрытые файлы и папки! Но опять таки, это не всем нравится, так давайте это выключим, пока родителикто-нибудь не испугался или не удалил нужных файликов. Для сокрытия в уже указанной команде поставьте 0 вместо 1. Ну и для примера, ссылка на статью, где описано много твиков с помощью этой команды.

Что-то типа заключения

Ну что ж, мы разобрали некоторые интересные возможности консоли в Mac OS X. Статья, разумеется, не претендует на полноту и является, скорее, «заманухой» для вовлечения маководов в shell-скриптинг да и вообще в консоль.